Processor Architecture

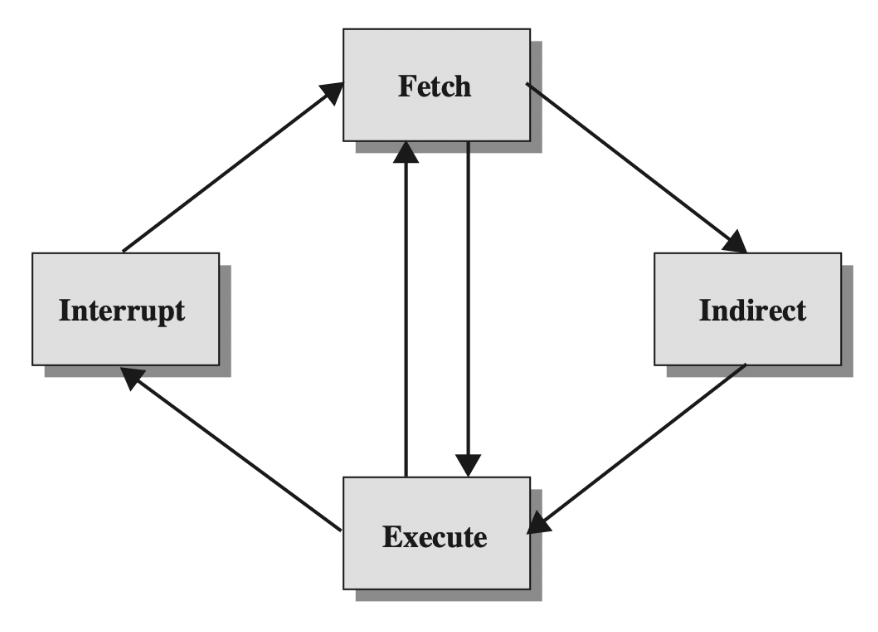

Instruction cycle

aka Fetch-decode-execute cycle

- Some instructions during the instruction cycle may require additional fetches. This makes the indirect cycle.

- We don’t always need to wait for an instruction to finish completely before fetching the next.

- Instructions can be prefetched during the idle memory cycle, when an instruction is being executed.

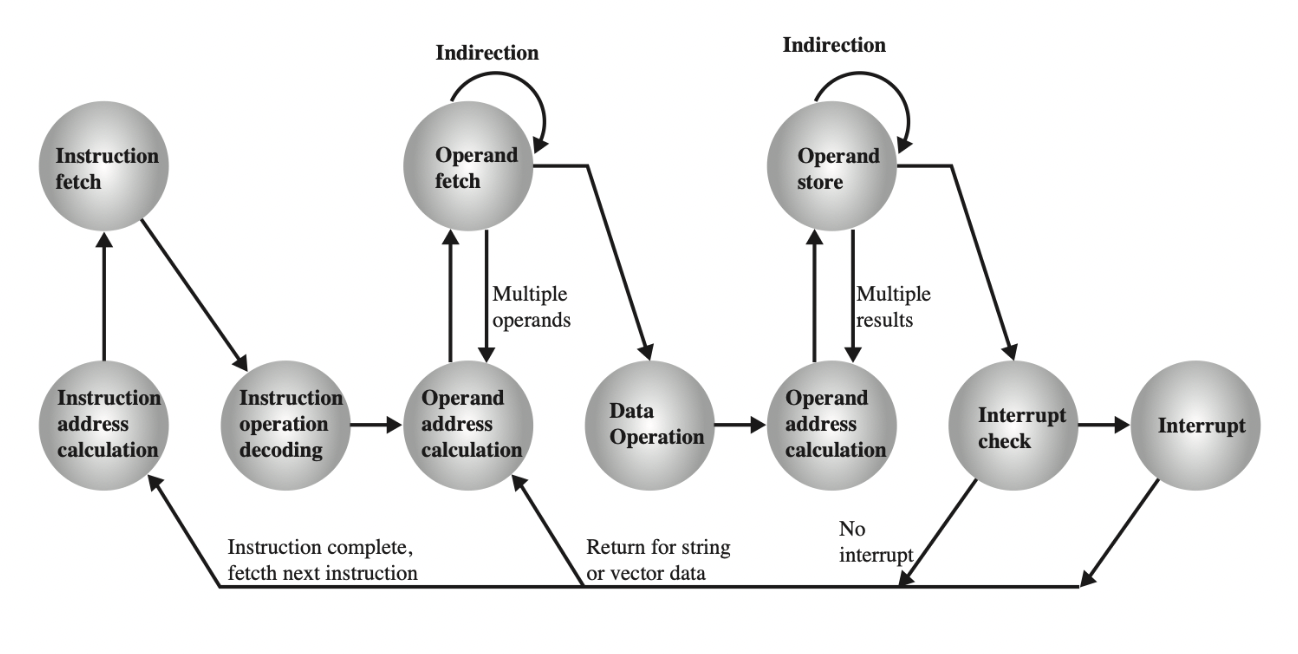

The indirect instruction cycle

The indirect instruction cycle

Control unit design

2 types:

- Hardwired CU: is a combinatorial ‘random logic’ circuit. Quickly transforms inputs to needed output signals, but is complex, inflexible, and requires a long design time.

- Microprogrammed: Uses a microprogrammed memory, which stores correspondances between inputs and outputs. Has it’s own PC, IR, and micro memory addresses (aww! cute). Slower, but is easy to design and implement, and can be reprogrammed in case of a vulnerability being found.

Microprogrammed control

- Each machine instruction is encoded as a sequence of microinstructions.

- Writable control store allows for microcode changes and emulation of different processors.

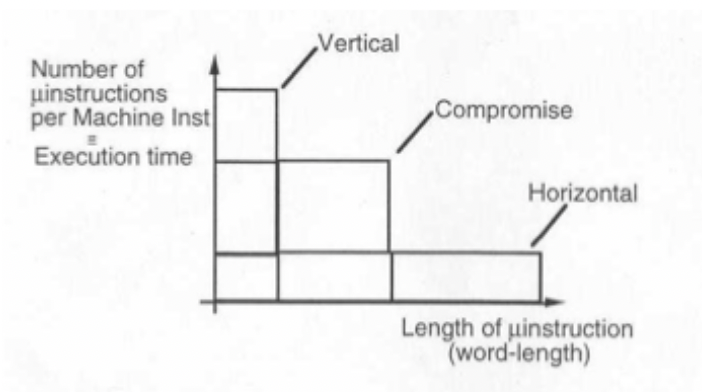

- Horizontal / direct control (unpacked): very wide microinstruction length, few microinstructions per machine instruction, fewer instructions therefore higher speed.

- Vertical control (Packed / encoded field): Narrow width, n control signals stored in log_2(n) bits, limited parallelism, but less complex circuitry.

- In reality a compromise is found between them; control signals get divided into groups

Microinstruction length vs number per machine instruction

Processor performace measures

- Instruction bandwidth in MIPS: Millions of Instructions Per Second

- Speedup = execution time on sequential machine/execution time on parallel machine

- Processor utilisation = speedup with n cores/n cores

- Data bandwidth in MFLOPS

Pipelining

- Using interleaved memory can ease memory contention in pipelining.

- 2 types of pipelining:

- Asynchronous: Uses handshake signals. Each stage signals when ready, and next stage signals back when ready to receive information.

- Synchronous: One timing signal, determined by slowest stage. All data moves at once. Has registers between stages.

Pipeline hazards

- Structural (resource conflicts): eg. 2 stages need to fetch from memory at the same time.

- Solution: Use interleaved memory, fetch data together where possible giving more free memory time.

- Control (procedural dependencies): Conditional branches stop us from prefetching instructions, since we don’t know what the next instruction will be. Solutions:

- Instruction pre-fetch buffers: Fetch both possible outcomes of the branch, select once path is known.

- Pipeline freeze: Don’t admit any more instructions to the pipeline until branch resolved.

- Static prediction: Predict always either branch taken or not taken (decision hard wired)

- Dynamic prediction: On the fly prediction.

- Branch instruction characteristics: Branch instruction indicates most likely way for the branch to go.

- Target address characteristics: Short / backward branches more likely to be taken, since they are characteristic of loops.

- Branch history: bits set or reset on outcome of execution are a good indicator of branch direction.

- Data hazards: When one (faster) stage uses information modified by a (slower) stage.

We can also pipeline execution units eg. adders to increase throughput.

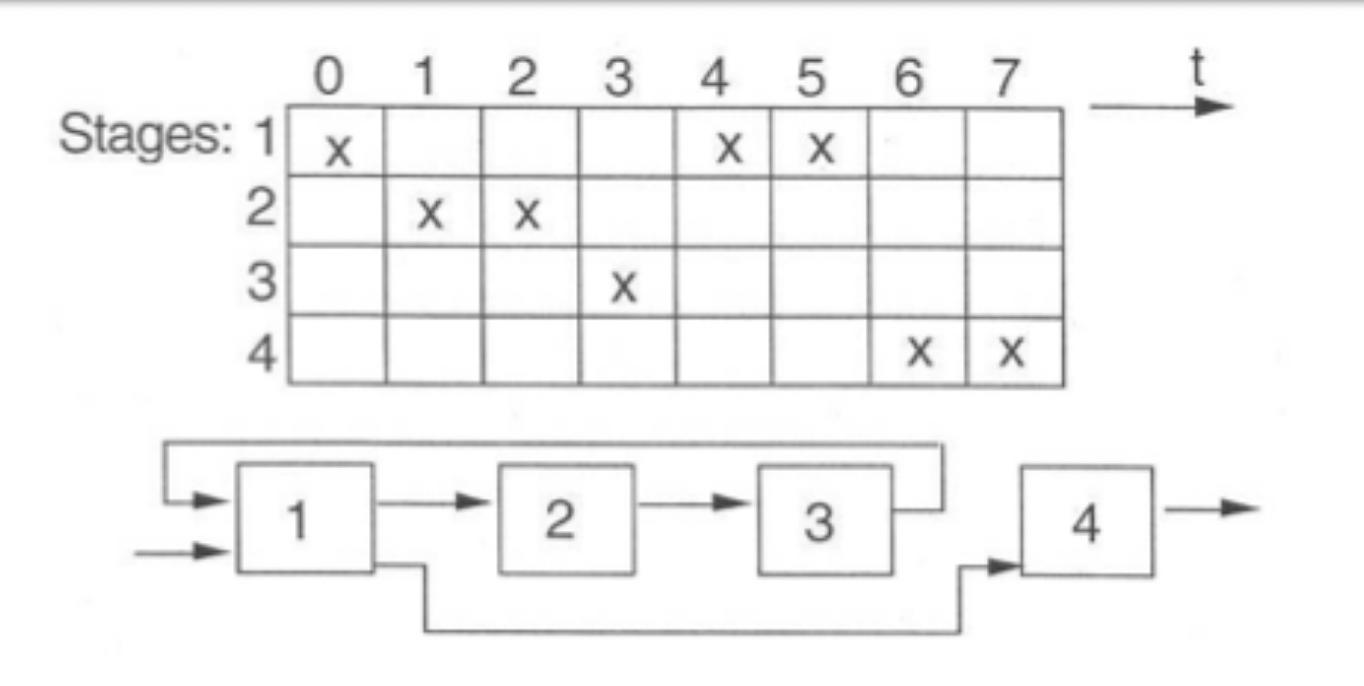

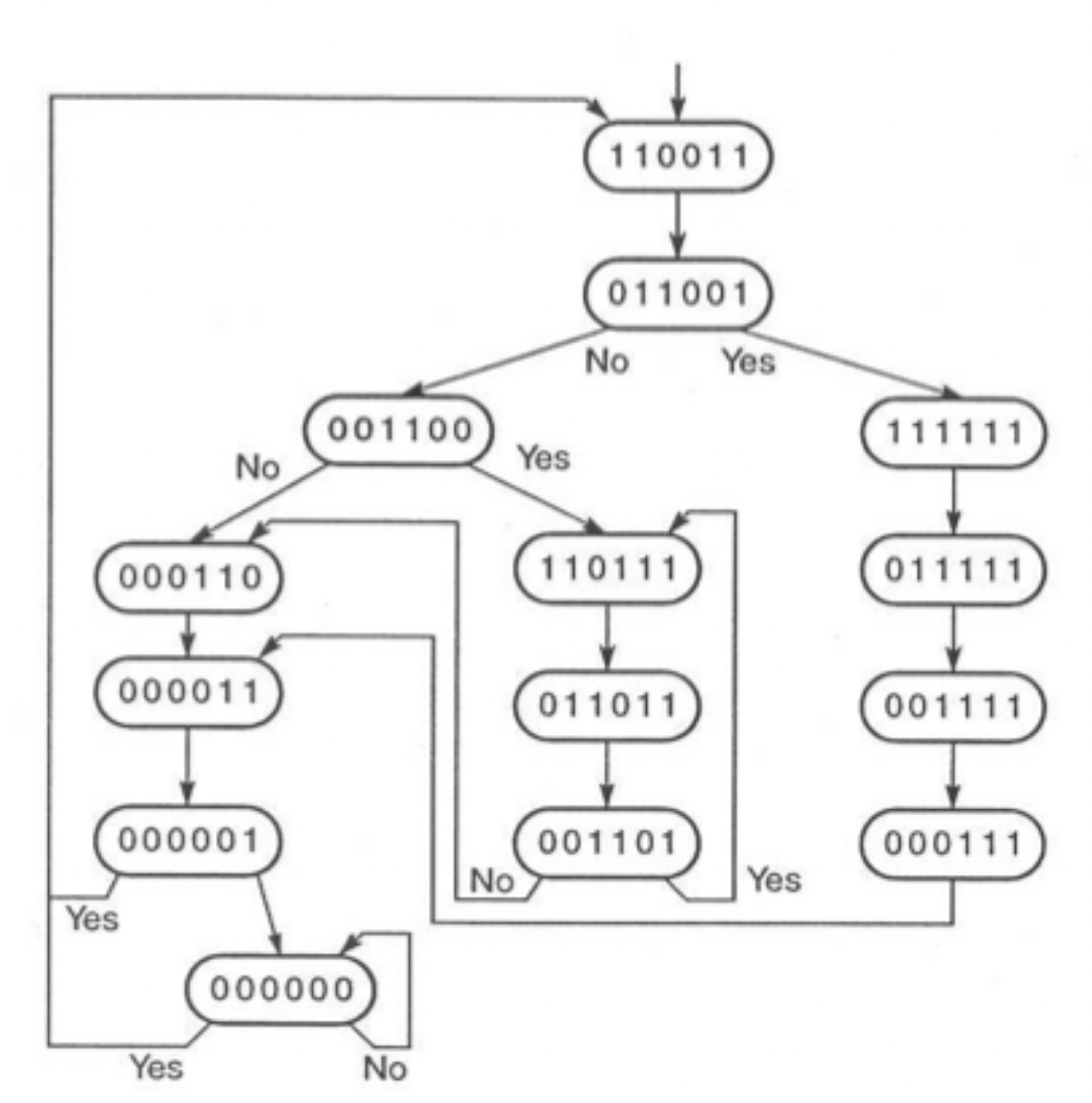

Reservation tables and collision vectors

- Initial collision vector derived from diagram.

- Count the distances between each pair in a row, and set the nth bit in the vector if there is a pair of that distance.

The initial collision vector here is 110011 (order 543210). 0 is always set.

- Using this, we can create a state diagram, and reduce it to it’s simple cycles.

State diagram

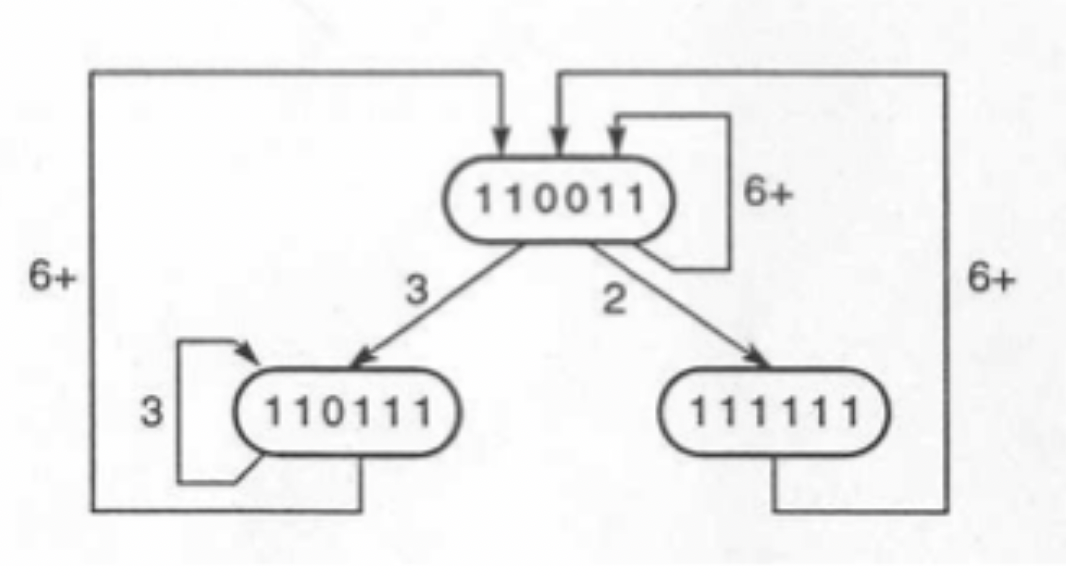

Simple state diagram

- Greedy strategy: always taking initiations when C0 = 0.

- Average latency for a greedy cycle ≤ No. of 1s in initial collision vector.

- Minimum average latency ≥ Max. no of Xs in reservation table row.

- Average latency = average of simple cycle lengths

- We add delays to the reservation table based on maximum number of parallel processes allowed (defined by minimum average latency)

I’m actually not too sure how this works lol - Felix

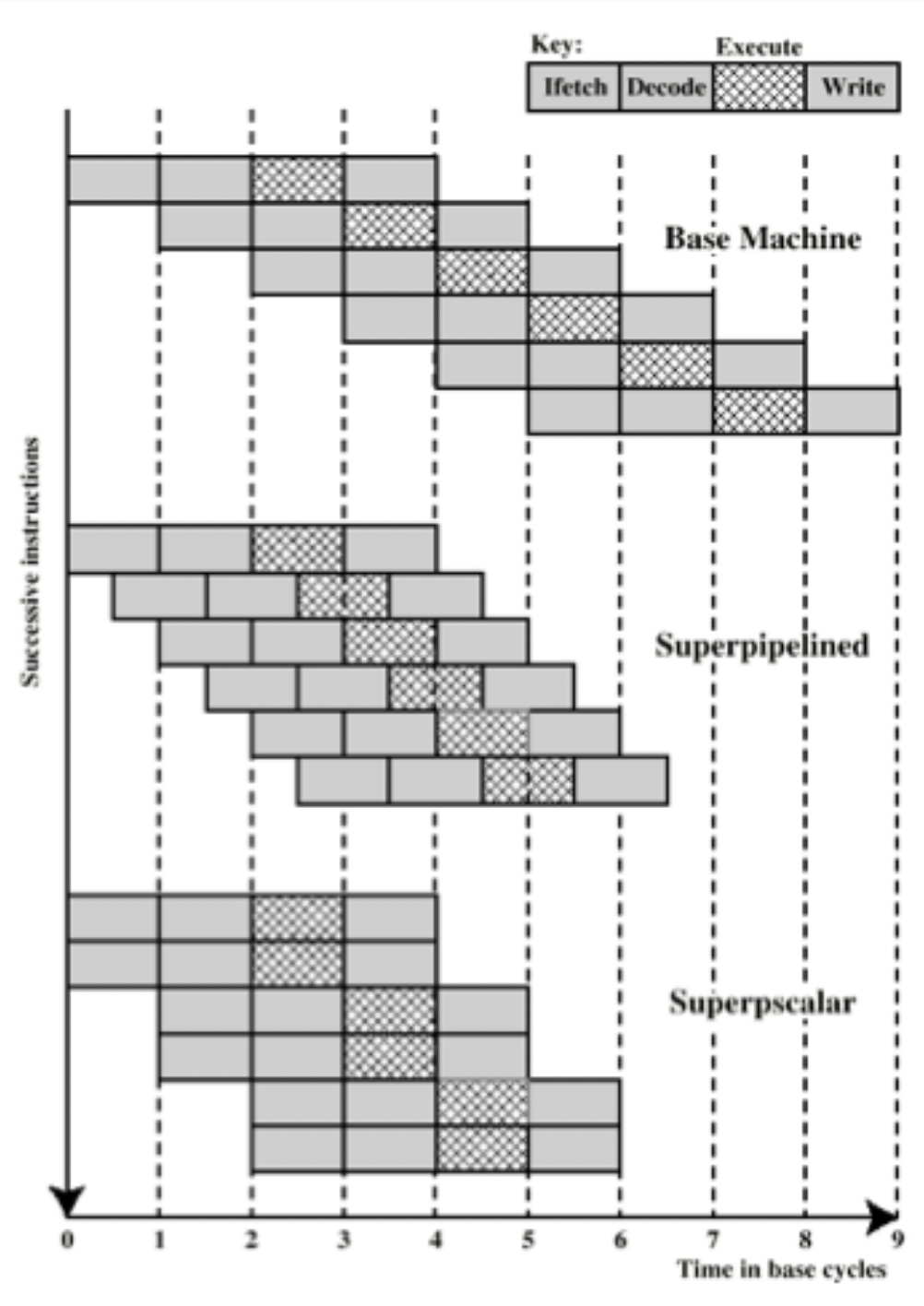

Superpipelining

- Some pipeline stages need less than half a clock cycle to execute

- We can douple the clock speed for them, getting double the throughput; this is superpiplining.

Superscalar

- Superscalar is fetching and decoding more than one instruction per cycle. This is achieved by having many functional units.

- σ = degree of superscalar. Avg. number of instructions issued cannot exceed σ.

- Uniform superscalar: Duplicate whole base pipeline.

- Non-uniform: Different amounts of different functional units.

- Superscalar allows for parallel fetch and decode operations.

- Speedup of superscalar processors is limited by instruction level parallelism.

Superpipelining vs Superscalar

Superscalar execution

- Program to be executed consists of linear sequence of instructions

- Instruction fetch stage forms a dynamic stream of instructions, which are then dispatched into the window of execution

- Processor executes them according to data dependencies and hardware availability.

- Finally, results of instructions are put back into order. Speculative branches are removed if the sequential model determines they should not have occurred.

Instruction level parallelism

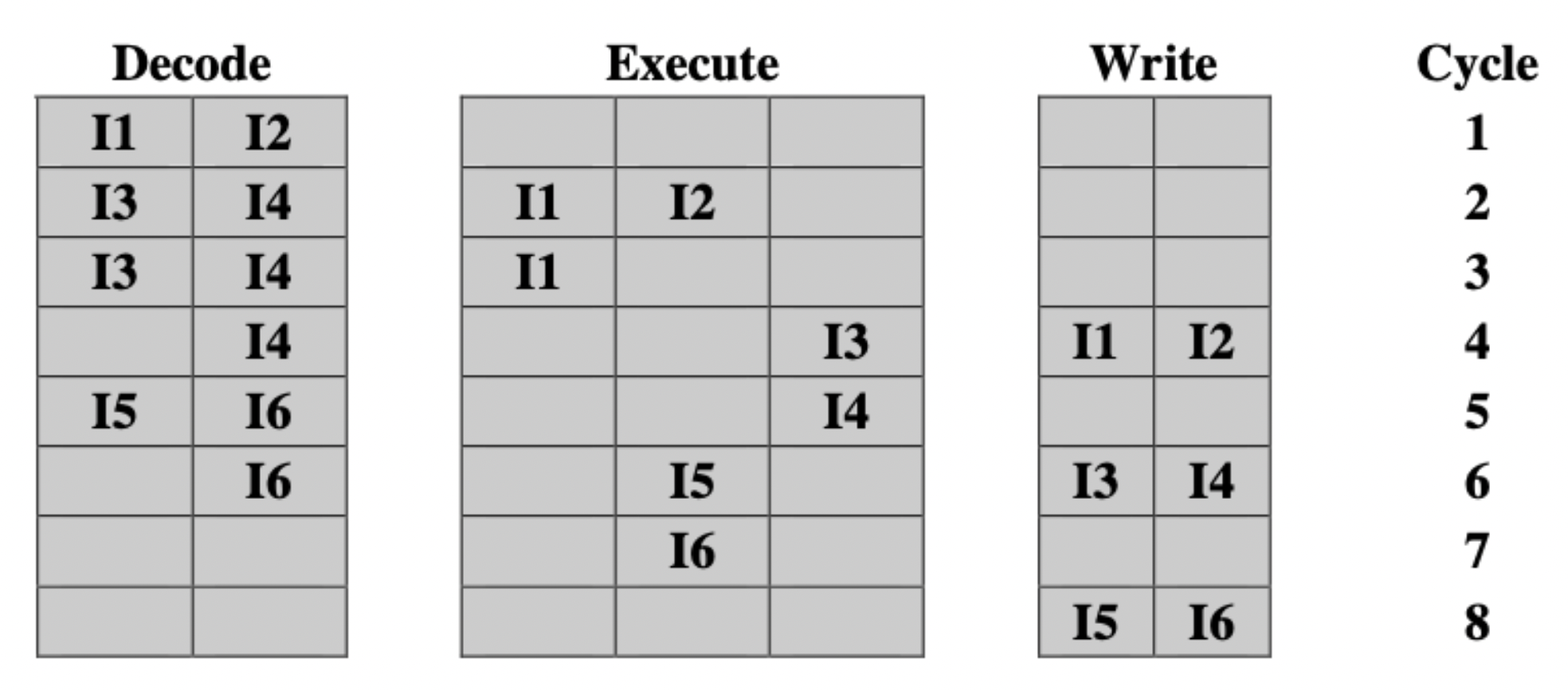

Out of order execution

- Significant types of instruction order: Fetch order, execution order, order of updating memory locations. 3 main policies:

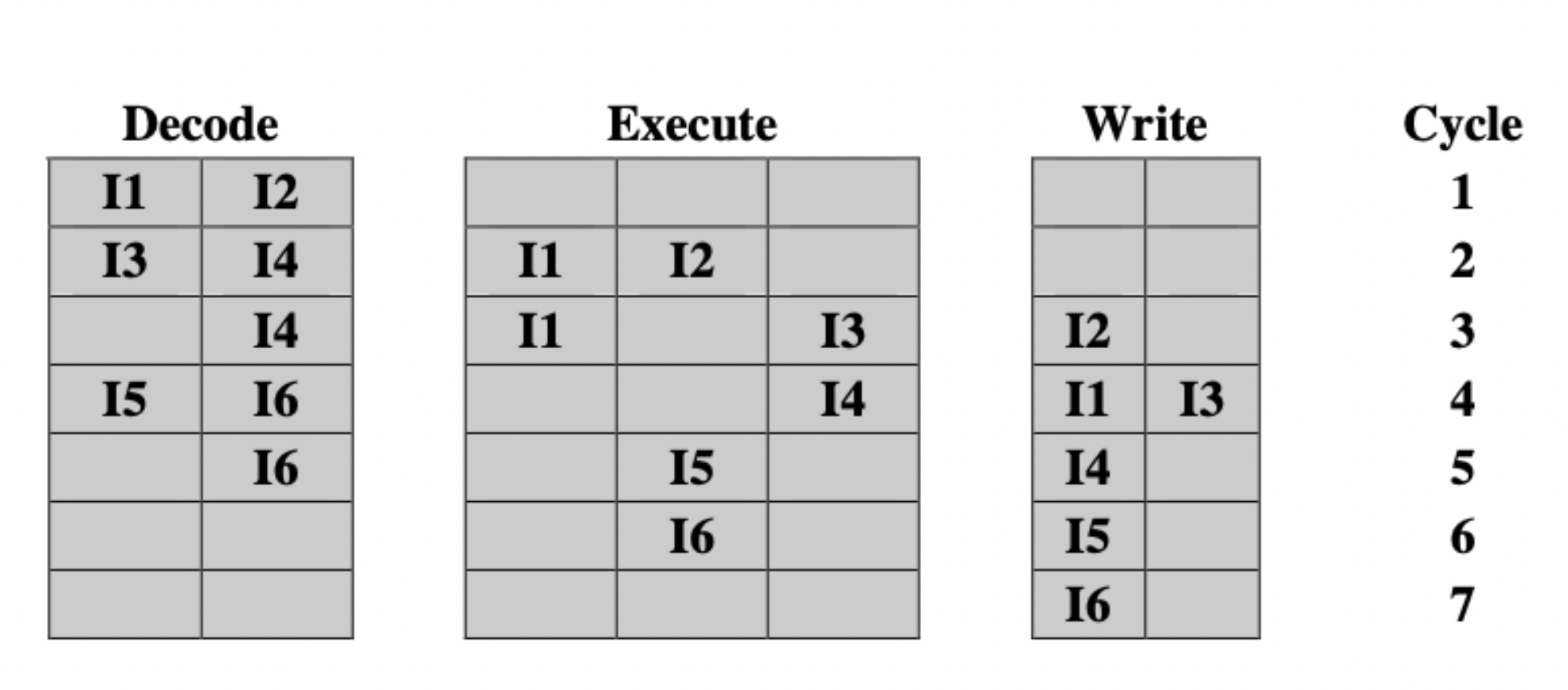

- In order issue, in order completion: wouldn’t be considered for a modern system. Instructions issued in the same order as they are executed.

In order issue, in order completion.

- In order issue, out of order completion: Any number of instructions can be in execution stage at once, but issue still stalled by resource conflicts, true data dependency and procedural dependency. Decodes up to a point of conflict.

- Introduces output dependency: Instrustion B must wait for the result of Instruction 1 to start execution.

In order issue, out of order completion.

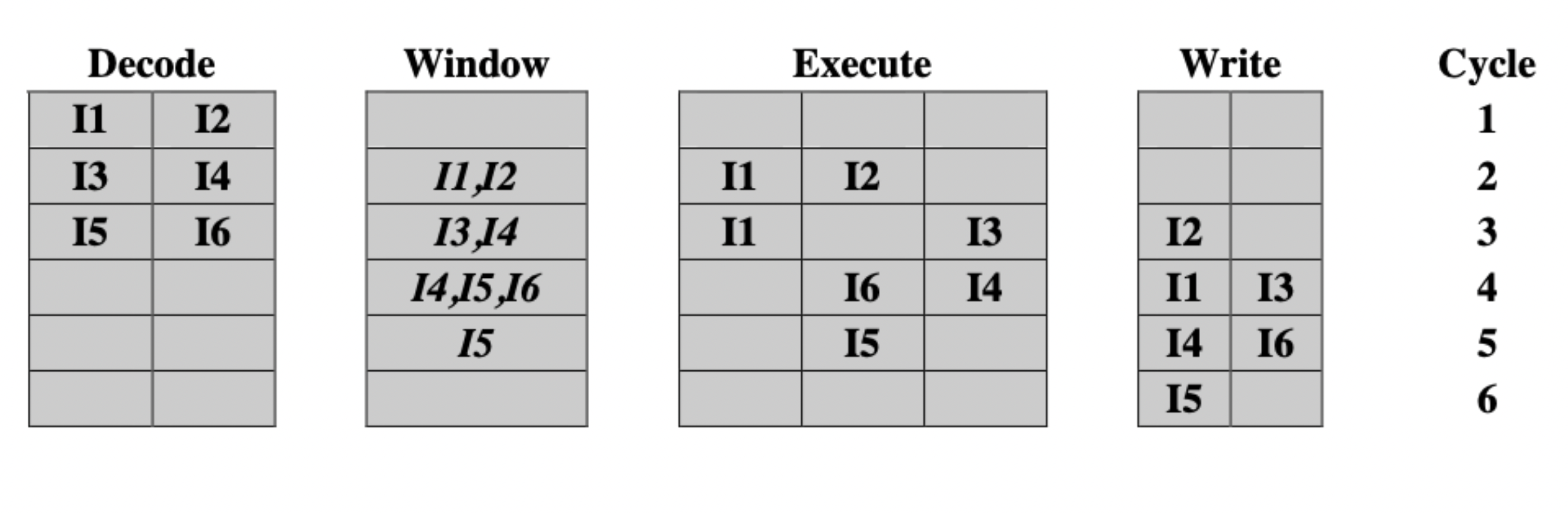

- Out of order issue, out of order completion: instruction window holds instructions after decoding, allowing processor to continue decoding during a conflict.

- Lets conflicting instructions begin execution, as long as they don’t finish before instructions effected by the conflict have started (i.e. fetched operands).

- Introduces antidependency: Instruction B, which modifies variable V, cannot complete before Instruction A fetches the old value of V.

Out of order issue, out of order completion.

Register renaming

- Output dependency and antidependency can be treated like a resource conflict.

- We can solve this by duplicating the resource i.e. register renaming.

- Subsequent instructions accessing the duplicated register are changed to refer to the duplicate.