Caches

We want to maximise cache hit ratio, i.e. amount of accesses where data is present in cache.

Cache mapping

- Direct: Maps each block of main memory to one possible cache line. Means that if two bits of data are mapped to the same cache line, one must be swapped out.

- Associative: Any memory block can be stored in any cache line, but cache logic must then search through every cache line to check if something is in the cache. Complex circuitry needed to do this in parallel.

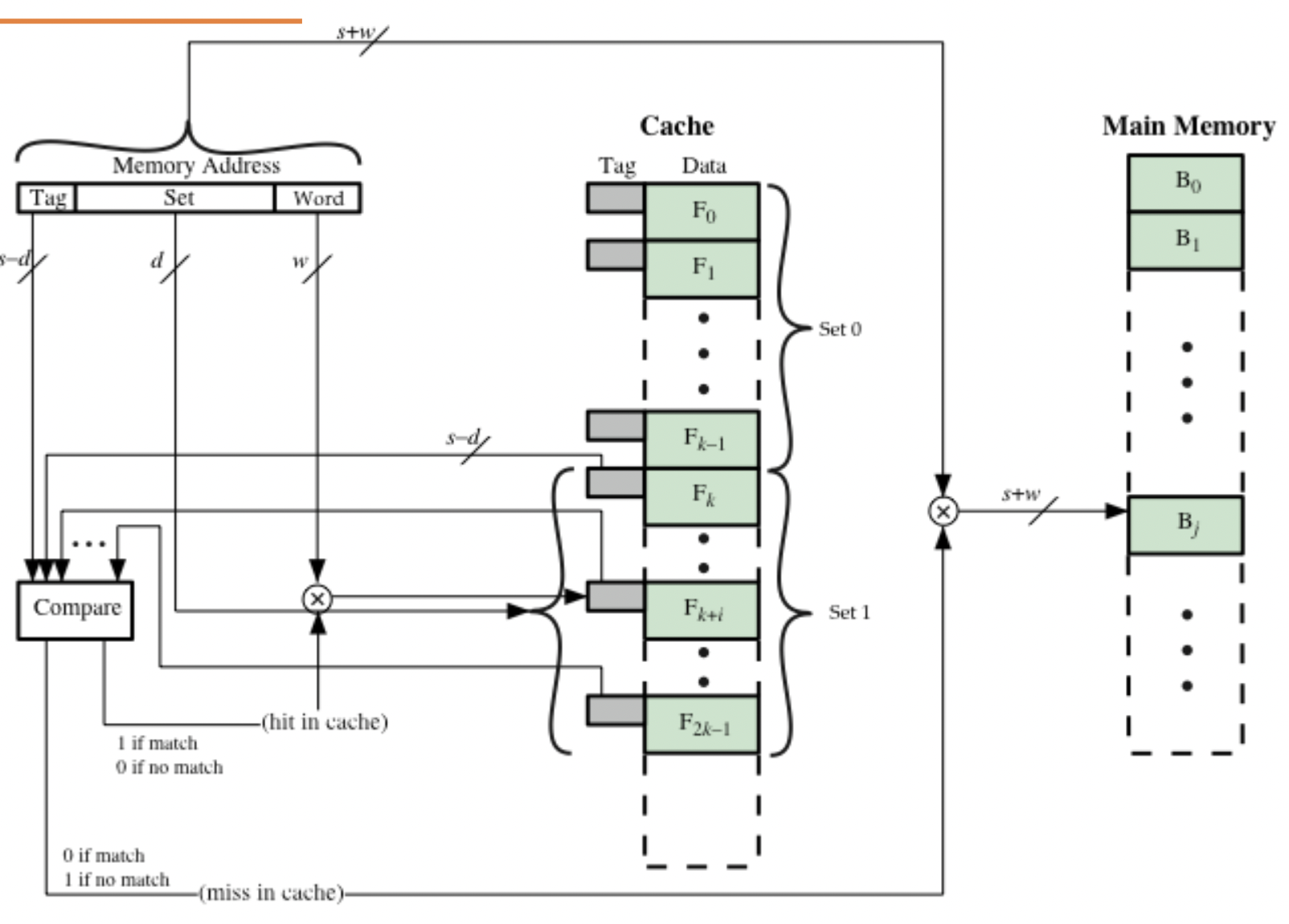

- Set associative: Every block maps to a set within the cache, but can be stored in any cache line within that set. Eg 4-way associative cache with 8 lines in each: each block can be in only 8 lines, rather than 32.

k-way set associative cache

Replacement algorithms used to decide which cache line to swap out in case of cache miss for associative caches. Best one to use is least recently used: replacement mechanism must be implemented in hardware, unlike page replacement.

Types of cache miss

- Compulsory: Data has never been retrieved before therefore not yet in cache.

- Capacity: Cache not big enough to contain all data needed during execution.

- Conflict: Caused by non fully associative caches’ placement policies conflicting.

- Coherency (multiprocessor only): Missung due to cache flushes

Multilevel caches

- Victim caches were used as an approach to reduce conflict misses, by storing all blocks evicted from the higher level cache. Nowadays this is done by an L3 or L4 cache.

- L1 contains a subset of L2’s data, L2 contains a subset of L3 etc. On eg. L2 cache miss, new data is written to both L2 and L1 caches, by the principle of inclusion.

Cache coherency

- Write through: Every write to cache is simultaneously written to main memory, keeping the two coherent. This means main memory writes dominate the write time.

- Buffers can be used to enhance this policy, freeing the cache for subsequent accesses

- No fetch on write policy: when no cache space is allocated on write miss, and change only written to main memory. Improves average access time further.

- Write back: writes to main memory only performed at block replacement time. Increases overhead of swaps but massively decreases overhead on every write.

- Tagged write back: only write back if the contents have changed between loading into cache and writing back.

Statistical exploitation

- Temporal locality: Keeping recently used data in cache, since likely to be used again

- Spatial locality: Load data near in memory to previous accesses; most accesses are within ±2kb of previous access

- Sequential locality: Since programs are sequential, more likely than not that the next data access will be the sequentially next data in memory

Cache optimisation

Simple techniques

- Larger block sizes: exploits spatial locality.

- Larger caches: reduces capacity misses, but can cause longer hit times and increased power consumption.

- Higher associativity: reduces conflict misses, but can cause longer hit times and increased power consumption.

- Multilevel caches: reduces miss penalty.

- Prioritise read misses over writes: read-after-write allows write buffers to hold updated location needed on read miss. Sending read before writes can therefore reduce miss penalty.

- Avoiding address translation during cache indexing: reduces hit time by using page offset to index cache instead of TLB. However, this imposes restrictions on cache structure.

Advanced techniques

- Control L1 cache size and complexity: using less associativity can reduce hit times, allowing for higher clock speeds.

- Way prediction: Uses block predictor bits to predict which set will be accessed next. If correct, gives speed of direct mapped cache.

- Pipelined cache access: Trades fast clock cycles and high bandwidth for slow hit times (increased latency).

- Non-blocking caches: Allows processor to issue more than one cache request at a time, so cache can be used whilst fetching data for a miss. Good for out-of-order execution.

- Multi-bank caches: Increases cache bandwidth. Similar to interleaved memory.

- Critical word first: Allows requests for certain words from a cache line to be delivered first, whilst rest of the line gets sent to processor.

- Merging write buffer: An empty write buffer can be used to store data with address to avoid the need to wait for data to be written back to main memory before allowing the data to be loaded into other layers of the heirarchy.

- Hardware prefetching: On miss, fetch two blocks, the missed block and the squentially next one. Prefetched block loaded into instruction stream buffer. This block can then be read quickly from ISB if needed later, rather than from main memory.

- Compiler driven prefetch: Compiler inserts prefetching instructions based on predictions about the program.

Compiler cenric optimisations

- Loop interchange: change the order of nested loops to ensure sequential data access, exploiting spatial locality.

- Blocking: Access multidimentional arrays in ‘sub-matricies’, meaning less data needs to be in cache at once, exploiting temporal locality.